The Washington Times, June 29, 1902, Magazine Features, Page 2

ELIZABETH VAN LEW, THE FAMOUS UNION SPY OF RICHMOND

Throughout the War She Carried on a System of Intrigues Which Displayed Marvelous Astuteness and Adaptation of Means to an End—Tireless Energy, Sleepless Vigilance, and Daring Intrepidity

Her Old Home in the Virginia Capital, Which Once Sheltered Hundreds of Union Soldiers, Now Converted Into a Club House for Men, and Is the Mecca for Thousands of Tourists—No Stone Marks Her Last Resting Place

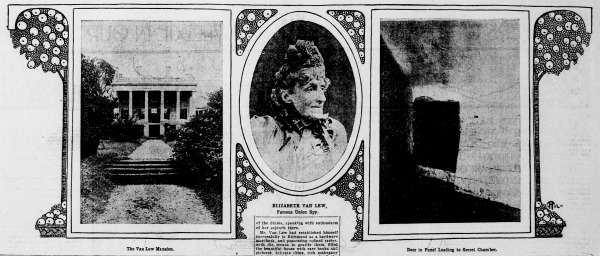

The spot in Richmond at present most frequented by strangers is the old Van Lew house, lately owned and occupied by Miss Elizabeth Van Lew, the famous Union spy, who rendered more assistance to the Federal Government during the civil war than any woman within the confines of the Confederacy, and carriages filled with tourists empty themselves daily before its entrance.

The place, purchased since her death, eighteen months ago, by an organization and converted into a clubhouse for men, has been renewed without being essentially altered, and here may still be seen the hollow ornamental columns on either side of the parlor mantel in which were concealed communications from General Grant and the authorities at Washington; the attic where fugitives from Libby Prison awaited an opportunity of escape through the lines; the secret chamber beneath the eaves into which they crawled when discovery threatened; the outlet through the roof for sudden flight when detection was imminent, and the strange figure on the basement wall of the mistress of the mansion herself which started out upon the application of some renovating chemical like writing with sensitized ink when exposed to fire.

In the Olden Style.

The house, built in 1799 by Dr. John Adams, for many years mayor of Richmond, and the son of Col. Richard Adams, a member of the House of Burgesses, fronts upon Grace Street. Its stuccoed walls, with trimmings of Scotch sandstone, brought over as ballast in pre-Revolutionary ships, rising three and a half stories high, and enclosing halls and rooms of stately proportions. It is approached by twin semicircular stairways, with carved iron balustrades, leading up on either side to a massive stone porch; and ascending them, and passing through to the rear, one steps out upon a broad plaza, commanding an extensive and exquisite view. In the distance, with graceful curve and musical cadence, flows the historic James, while at one’s feet stretches a fragrant, terraced garden, shaded with magnolia, walnut and elm trees, the homes of squirrels, and song birds, nestling in trunks and branches. Gravel walks, hedged high with boxwood, wind everywhere, leading out to summer house and rustic seats, and down to a moss-covered spring which bubbles below.

John Van Lew, Owner.

During Dr. Adams’ occupancy tradition tells of such visitors as Chief Justice Marshall and his distinguished contemporaries, while General Layfayette was his house guest during his stay in Richmond in 1824. After his death, too, when in 1834, John Van Lew, a native of New York and the descendant of an old Knickerbocker family, purchased the property and brought his young family there to live, it was still the center of a cultured circle. Fredrika Bremer, the Swedish authoress, who made the tour of the States, speaking with enthusiasm of her sojourn there.

Mr. Van Lew had established himself successfully in Richmond as a hardware merchant, and possessing refined tastes, with the means to gratify them, filled the beautiful house with rare books and pictures, delicate china, rich mahogany and Chippendale furniture, and all the rest of the accessories of wealth and culture; and his luxurious coach, drawn by four white horses, in which the family went every summer to fashionable resorts, is still remembered by the older citizens. His wife was a daughter of Hon. Hillary Baker, once mayor of Philadelphia, a circumstance which led to her own daughter—destined to become so famous—being educated there; and this, in turn, to her adoption of the anti-slavery sentiments which shaped her course during the war. Her intimacy with Miss Bremer, too, a pronounced Abolitionist, tended to emphasize her views and during her visit to her the two drove to the “slave-selling houses” and negro jails in Richmond, Miss Van Lew, whom the authoress describes as “a pale, pleasing blonde,” weeping over the sufferings of the inmates and winning her heart by her interest in them.

Her Success as a Spy.

Had her father lived, according to one who knew them both, this interest would have found a different outlet. He died in 1860, however, and at the breaking out of hostilities a year later, his daughter inaugurated a system of intrigues, which whether we decry or applaud it, according to our viewpoint, must still be admitted to evince, not only marvelous astuteness and adaptation of means to an end, but tireless energy, sleepless vigilance and daring intrepidity.

During the years when the Federal army thundered at the gates of Richmond she was in constant communication with it; and when Grant hovered in its vicinity she kept in such close touch with him that flowers cut from her garden in the morning adorned his table at the evening meal. She spied upon the Confederacy and all of its agents, both civil and military, contriving to install her deputies in the household of President Davis as servants, and through them to acquaint herself with the result of his conferences with his cabinet. The information thus obtained was put in cipher, and, concealed between an outer and inner sole of his shoe, was smuggled through the lines by a negro employed on her farm, below the city, his humble station enabling him to pass in and out unmolested by the guards.

She was also in touch with the inmates of Libby prison, ingeniously supplying them with implements with which to work their way out, and harboring them until an opportunity to elude the Confederate pickets presented itself, and was the abettor of Colonel Streight, the noted raider, who tunneled an “underground passage and with 1,800 prisoners, made his escape.

Her services in the cause of the Union were not positively and fully known, however, until after her death, when ex-Federal officers, who had been concealed in her house—one of whom now occupies a Government position in Washington—visited the place and disclosed the secret chamber and the movable step leading out through the roof. That her services were recognized by General Grant is evinced by the fact that, upon hearing of the evacuation of Richmond, he dispatched his aide-de-camp, Colonel Parke, to see that she was properly cared for, paid long visits to her at her home. One of his first acts, too, after he became President, was to make her postmistress of Richmond, a position which she held for eight years, and her receipts from which amounted to $30,000. She later had a Government position in Washington, which she retained until Cleveland came into power, when she resigned. Her mother died in 1870, after which her home was shared by her brother and his two daughters. One by one they passed away, however, leaving her at the last alone in the old house, haunted by the memories of more than a century. Her course during the war, and her affiliation with negroes after it, alienated the people of Richmond, who withdrew from all association with her. Only one or two close friends continued to cling to her; and her pathetic plaint, when sickness and old age had overtaken her, was: “I’m so lonely; nobody loves me.”

No stone marks the green mound beneath which she sleeps in Shockoe Hill Cemetery, but a strange coincidence identifies it. The space reserved for her in the family lot was insufficient to admit of her grave being dug in the usual way, and it lies north and south, as did those of the Federal soldiers buried in Confederate cemeteries, as did that of Ulrich Dahlgren.

- Details

- Categories:: Other Newspapers After 1865 Elizabeth Van Lew Unionists and Spies Libby Prison Libby Prison Breakout Escapes Residences and Homes Politics Shockoe Cemetery

- Published: 31 October 2017